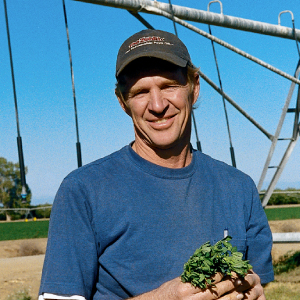

Bert Weststeyn

"When they're running I can sleep better at night since I'm not worrying about checking flood sets or having a system stop due to an electrical problem."

“We Couldn’t Grow Good Alfalfa Hay On This Ground Without Linear Irrigation”

Who could argue with Bert Weststeyn’s observation about the importance of irrigation in general and for producing quality alfalfa hay in particular: “It doesn’t grow here without it.”?

An irrigator for 20 years, Weststeyn has been flood irrigating with siphons for much of that time. Now, in addition to his dairy further south, he’s finishing year two at a second and newer location near Willows, California.

At Willows, he has 300 acres under two T-L linear irrigation systems, and he plans to install another linear on the remaining 113 acres that he’s been flood-irrigating.

“We couldn’t grow good alfalfa hay on this ground without linear irrigation,” describes his experience at the new location.

“The main reason I’m converting to linear irrigation is that’s it’s really hard to get a good stand of alfalfa established when you flood irrigate,” he points out. “It’s much easier to get a stand established under a sprinkler, even with a spring seeding.

“The old-timers say,” he adds, “‘It’s going to take a whole year to get your hay established’. We don’t have that uch time, and even then there are big problems with flood irrigating alfalfa.”

Weststeyn says he’s found that if flood irrigation water is applied when the air temperature is high, even at night, the alfalfa burns. Also, the ground can soak up so much water it’s often,”too saturated for two weeks and then too dry.”

Another trouble he experienced with flooding was that there were always some wet spots in his fields. Weeds liked to take root in the wet areas as well.

“With linear irrigation the greater uniformity of water application is readily evident to the eye,” he says. Another factor is the time involved between a post cutting irrigation and the next cutting coming along. Flood irrigation often locked him in to making a choice between hay quality or volume, according to Weststeyn.

“It’s a lot easier to control your hay quality when irrigating with a linear rather than flood irrigating,” he points out. “A linear lets me be much more flexible.”

“For example, say I want a little more tonnage in a cutting. If I attempt that by flood irrigating I have to apply nine inches of water an acre, then wait an average of 14 days to harvest it for either hay or haylage.”

On the other hand, he’s learned he can cut back the linear to a half-or three-quarter-inch an acre application, and still begin harvesting two or three days later. Or, he can decide to put on another inch or so of water and cut four or five days later.

“So, being flexible can boost my alfalfa hay tonnage a quarter-ton an acre while retaining the hay’s quality. The bloom stage is about the same. Applying a flood irrigation would put the crop “way past the bloom stage I want” Weststeyn usually applies one-and-one-quarter inches of water seven times after each cutting via linear system. This results in an eight-plus tonnage annual yield of hay. He estimates that compared to typical flood irrigation, linear irrigation represents annual water savings of 30 percent.

Then there’s the labor angle, which Weststeyn says is also definitely in favor of linear. As he says, “Flood irrigation takes a lot of labor, working 24 hours a day. It’s always hard getting a night irrigator since few people want to do this job.”

“Of course, you can decide to not irrigate at night and just put water on during the daytime. But, then it takes much too long to get all the field watered.”

Conversely, once the linear system is started it runs day and night by itself with little more to be done than infrequently checking its operation. As Weststeyn notes, “This saves us the labor of at least one man, and maybe the equivalent of one-and-a-half hired men.”

“Anymore, finding good help is the most difficult part of farming,” he shrugs. “If you can’t do the work yourself, you have to rely on hiring help. So, in many ways a linear system makes farming easier, faster, and a lot more enjoyable, plus it saves water.”

When Weststeyn was initially considering making an investment in two linear irrigation systems he placed emphasis on trouble-free reliability. A linear system “down” too long would certainly lower yields and possibly contribute to damage of an alfalfa stand.

“That’s why I went with the T-L linear irrigation systems,” he comments. “They’re hydrostatically instead of electrically driven, have fewer moving parts and no microswitches, and so are easier to understand and work on if need be.”

“When they’re running I can sleep better at night,” Weststeyn smiles, “since I’m not worrying about checking flood sets or having a system stop due to an electrical problem.”

WHY CALIFORNIA Farmers Like Linear Irrigation

Although in most other parts of the country the center pivot is easily the most popular mechanized irrigation system, California farmers prefer linear systems. Weststeyn explains that while a linear system is easily the more expensive of the two methods, every acre in the field receives irrigation water. Center pivots leave four unirrigated corners. In other areas there’s generally enough summer rainfall to produce some sort of yield from crops planted in the dryland four corners. However, he says that doesn’t make economical sense in California since rain is seldom seen during the typical growing season.